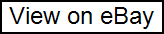

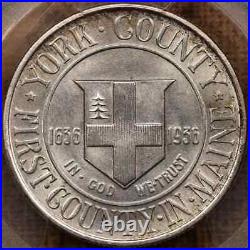

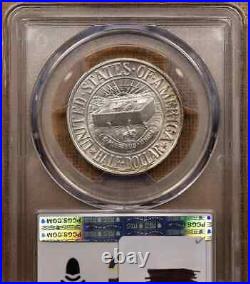

PLEASE FOLLOW OUR E BAY STORE. PLEASE READ WHOLE ADD. We do not want your feed back. We want your repeat business. We get by having best prices on the net. 1936 NORFOLK COMMEMORATIVE HALF DOLLAR. COIN US GRADED MS67 BY PCGS. THE ITEM PICTURED IS WHAT YOU WILL RECEIVE. 50 cents 0.50 US dollars. 30.61 mm (1.20 in). 2.15 mm (0.08 in). 1937 (coins bear the date 1936). 25,000 with 13 pieces for the Assay Commission. None, all pieces struck at the Philadelphia Mint. City seal of Norfolk, Virginia. And Marjory Emory Simpson. Norfolk’s ceremonial mace. The Norfolk, Virginia, Bicentennial half dollar is a half dollar. Struck by the United States Bureau of the Mint. In 1937, though it bears the date 1936. The coin commemorates the 200th anniversary of Norfolk. Being designated as a royal borough. And the 100th anniversary of it becoming a city. It was designed by spouses William Marks Simpson. Virginia Senator Carter Glass. Sought legislation for a Norfolk half dollar, but the bill was amended in committee to provide for commemorative medals instead. Unaware of the change, Glass and the bill’s sponsor in the House of Representatives, Absalom W. Shepherded the legislation through Congress. Local authorities in Norfolk did not want medals, and sought an amendment, which passed Congress in June 1937. The legislation required that all coins be dated 1936; thus, there are five dates on the half dollar, none of which are the date of coining, 1937. The Norfolk half dollar is the only U. Coin to depict the British crown, shown on the city’s ceremonial mace, found on the reverse. (“tails” side) of the coin. Much of the area now comprising the city. Was granted by Charles I of England. In 1636 to Adam Thoroughgood. A former indentured servant. Who had risen to become a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. Thoroughgood recruited 105 people to live on the land, and named the area for his birthplace, the county of Norfolk. Some land was granted to the Willoughby family; this eventually became Norfolk’s downtown. In 1736, Norfolk was granted a charter as a royal borough by George II. And the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia. Presented Norfolk with a ceremonial mace. In 1753, making Norfolk the only American city to have a mace from colonial times. Despite being nearly destroyed during the American Revolutionary War. Norfolk was almost as large a port as New York City by 1790, but its importance declined in the 19th century. It remains home to a major naval base. In the case of the Norfolk half dollar, the responsible group was the Norfolk Advertising Board, Inc. Affiliated with the Norfolk Chamber of Commerce. Introduced a bill for a Norfolk Bicentennial half dollar on May 20, 1936; it was referred to the Committee on Banking and Commerce. The bill was reported back to the Senate by. Of Colorado on June 20. The committee recommended in the report that a medal, not a coin, be issued. They attached a 1935 letter from President. Complaining that commemorative coins of a purely local nature were being authorized by Congress, and recommending that commemorative medals be issued instead. We haven’t quit the fight. We’ve asked an appointment with President Roosevelt for the purpose of discussing the matter and laying Norfolk’s claim squarely before him. We have a right to know why Norfolk has been discriminated against. It’s time for the people of this area to rise up in righteous indignation at this insult to the city. The past session of Congress passed bills and the President signed them authorizing the issuance of fifteen commemorative coins. Is the landing of the Swedes in Delaware of more historical importance than the original land grant for Norfolk county, comprising what is now Norfolk, Princess Anne and Nansemond counties, and embracing what historians recognize as the most historical area in the country? Is the settlement of northern Illinois, commemorated by the Elgin issue, more important than the granting of the royal charter to Norfolk City? Why, after all these commemorative coins had been authorized, should governmental authorities suddenly become so solicitous of their coinage that the Norfolk issue is so mysteriously changed to call for a medal? Something is radically wrong. And it’s time for the people of Norfolk to bring every pressure to bear in an attempt to remove what is in reality a direct insult to the city. June 20, 1936, the final day of the session, was an exceptionally busy day in Congress. After Adams reported the bill back to the Senate. Glass attempted to have it considered by that body, but initially Joseph Guffey. Of Pennsylvania objected, demanding the regular order. Later that day, Glass advised the Senate that Guffey had stated he would not further object, and again asked to have the bill considered. This time it passed without objection or debate, and the title was changed to reflect that medals were to be struck rather than coins. The bill was considered by the House of Representatives later the same day. Of Virginia moved that the House pass it, stating that the bill authorized medals, but when questioned by Robert F. Of Pennsylvania, stated that the bill was for “silver coins”. The House passed the bill without amendment or debate. And it was signed into law by President Roosevelt on the 28th. Such medals would have had no market, as collectors of the day preferred legal tender. Coins, which is what the promoters of the bill wanted, and so no medals were struck. It was at first hoped that the initial bill might be used to authorize coins; when this proved not to be the case, the head of the Norfolk Advertising Board, Franklin E. Turin, was interviewed in the Norfolk Ledger-Dispatch on August 5, and “ripped away the veil of secrecy that has shrouded negotiations and called a spade a spade”. Turin blamed Roosevelt for the mix-up, and stated that Senator Glass had said he had not realized the bill had been changed, nor had Representative Robertson. Senator Glass promised another attempt. Glass reintroduced the bill, this time numbered as S. 4, on January 6, 1937. It was reported back to the Senate on the 16th by Adams with an amendment containing language usual to commemorative coin bills, that the federal government would not be responsible for the expenses of preparing the dies. The Senate passed it without objection on January 19. The bill was transmitted to the House, where it was referred to the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures. That committee on May 26 reported the bill back, recommending that it pass after being amended, including increasing the authorized mintage from 20,000 to 25,000. The report drew attention to the “unfortunate error” of the previous year, and “that in making this favorable report it is merely helping to correct this oversight”. The House passed the amended bill on June 21 without discussion or dissent. Roosevelt signed the bill, authorizing 25,000 half dollars, on the 28th. Turin, August 5, 1936.